韻

May 19, 2025

/

Sydney

/

6 Min

There are words that explain, and there are words that echo.

韻 Yùn belongs to the second category.

I first encountered 韻 as a sensation - something felt and recognised.

It appears when you read poetry long enough that meaning stops asking to be solved. It is rarely the image that stays - but the moment after a verse ends, when the scene has already moved on without you. A soft internal settling and a residue. What remains is a pressure. As if something has crossed through your attention without asking for resolution.

後來我才知道,那個感覺叫韻。

韻 is often translated into English as resonance or rhyme, gesturing toward sound. But 韻 is really about what remains after sound has ended. It is the aftertaste of language - the warmth left in the mouth once the words are gone. The part that resists quotation, because it was never fully contained in speech to begin with.

古人說:言有盡,而意無窮。

Words end; meaning does not.

Much later, I recognised 韻 again in my Mum's calligraphy. Calligraphers speak of 神韻 - spirit resonance - something no amount of correctness can manufacture. To value 韻 over form, and while structure mattered, only insofar as it allowed the work to live beyond itself. A piece could be asymmetrical, unconventional, even imperfect - and still possess 韻. Perhaps especially then.

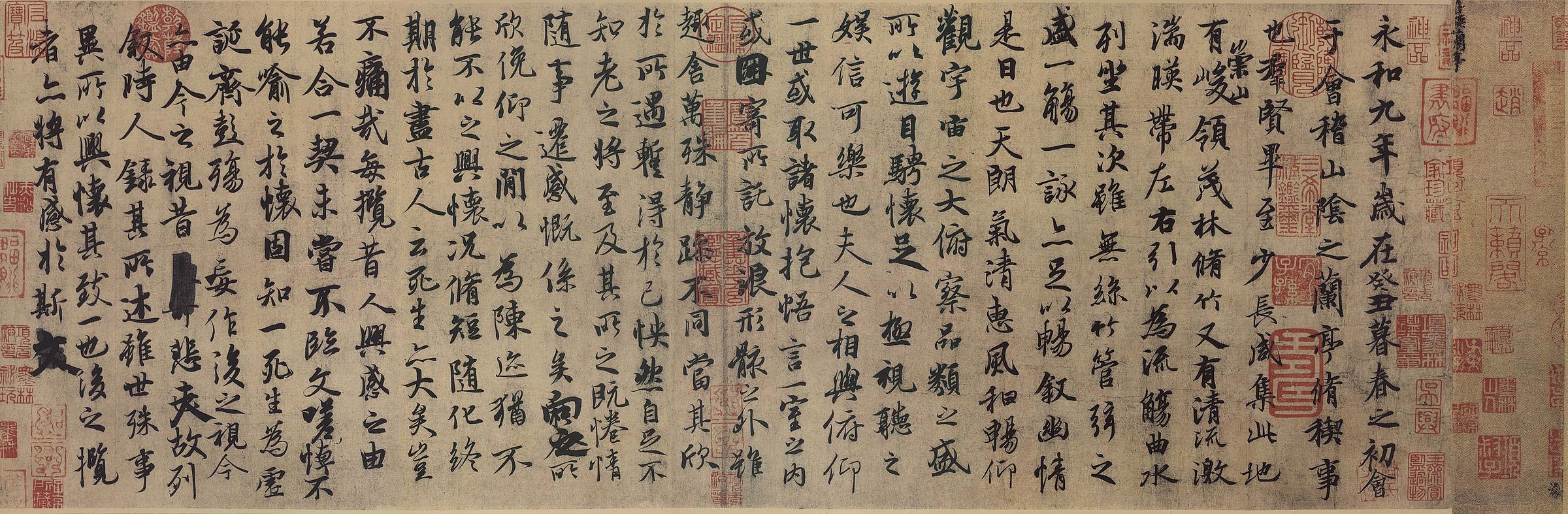

王羲之: 蘭亭集序 (Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering) is studied for the way it carries space, rhythm, and flow. It has presence that outlives every stroke

This juxtaposition stays with me.

There is an old idiom: 餘音繞梁 - the remaining sound circles the beams. It describes music so refined that its echo seems to hover in the room long after the performance has ended.

The phrase is not really about music.

I’ve noticed that people, places, and ideas tend to follow the same rhythm. Their meaning does not announce itself. Things that do not declare themselves immediately. Cities that reveal their logic only after you’ve stopped trying to master them. Conversations that feel unfinished, yet strangely complete. Sometimes the most important part remains unsaid, an idea which sits uncomfortably with instruction, but not with experience.

There is a discipline to this kind of presence - of knowing where to surrender. An endless practice.

有韻者,不喧。

That which has resonance does not need to be loud.

I think this is why 韻 resists English so stubbornly.

English tends to move toward outcomes.

It excels at naming results - success, clarity, impact -

and advances decisively toward conclusion.

This is not a flaw, but a cultural habit of articulation.

French lingers in proportion - justesse, retenue, élan -

allowing thought to hover rather than resolve.

Arabic privileges root and resonance,

where meaning unfolds through internal pattern,

memory carried inside structure.

韻 belongs closer to the latter traditions.

韻 emerges when effort has softened into ease, when intention has dissolved into instinct, depth over sharpness, volume over gravity. The long arc rather than the sharp turn. White spaces that allow meaning to breathe. Toward a presence that does not rush to define itself, because it trusts that what is real will reveal itself in time.

To ask oneself: will this still matter once the noise recedes? Will it echo, or merely register?